| O ZHANG |  |

Between Fiction and Reality

by Michèle Vicat

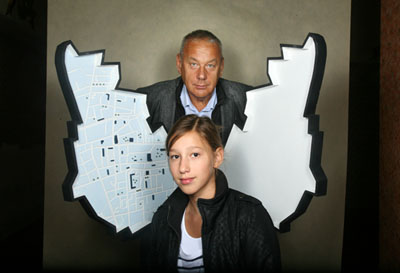

O Zhang photograph by George Argento© 2011 |

I became acquainted with O Zhang’s work in 2004 at the exhibition On the Edge: Contemporary Chinese Photography & Video, at Ethan Cohen Fine Arts’ Gallery in New York. Ethan Cohen asked me to hang O Zhang’s Horizon, an installation of twenty-one photographs. O Zhang was very precise about the placement of each photograph and the distance between them. She wanted them displayed in three rows of seven photographs each. In trying to meet her requirements, I had time to look at the images more closely.

|

My first impression, looking at the images, was that this was a simple documentary study. But when I placed one photograph next to another one, I had a sense that something else was taking place. The slow physical act of mounting the photographs revealed a tension between the subjects and raised questions about the kind of horizon that awaits them. O Zhang, born in China in 1976, has lived and worked in New York since the fall of 2004. She returned to China in the spring of 2004 to shoot Horizon. Her intention was to reunite with her childhood and to question the shift of power in today’s China. Her parents had been living in a remote village in Hunan Province for ten years before she was born. They had both been English translators, and as such were considered dangerous intellectuals. They were forced to work on a pineapple farm for “re-education.” Her mother had traveled to Guangzhou for the birth, and O Zhang stayed with her grandmother in Guangzhou until she was nine months old and was returned to her mother in Hunan. There, during her playtime with local children, the young O Zhang learned the languages of the Miao and Tujia minorities. It is with nostalgia that she remembers the period in her life when she could draw inspiration from nature. But nostalgia also leaves a taste of bitterness. A trace that the artist attempts to override by dealing with identity and history, two themes that repeatedly weave through her work.

For Horizon, O Zhang intentionally chose a village in Hubei that she had not previously known in order to go beyond the memories of herself as a displaced little girl. In most villages girls cannot escape as O Zhang did. “For this project, I was determined to have only girls from one village,” O Zhang told us. “Why little girls?” she continued. “Because myself I grew up as a girl in a village. I could feel the pressure and could see how boys were more valuable.” The artist selected girls between four and six years old, an age when educational opportunities are open to children in the West. In China, girls in poor villages risk being deprived of an education. For this series, O Zhang decided to make frontal portraits of these little girls in a natural environment. The result is striking: although crouching, the little girls are huge, nearly jumping out of the photographic frame. They look at us with an intensity that communicates their disbelief in a world of innocence that should have been theirs. The profound blue sky circumscribes the body’s mass of each one. There is something disturbing in O Zhang’s pictures. When the twenty-one photographs are aligned in the superposed three rows, we realize that all of the girls are looking at us, but from a different angle. The girls in the upper row are looking down at us. The girls in the middle row gaze directly at us. In the lower row, they look up at us. We are forced to enter into their world, which is far from a fairy tale. O Zhang likes to confront us with our own clichés. In a “normal” world, little girls are cute and we are ready to do anything for them. In Horizon, the girls have no artifice to offer: they are the ones rejected because of their sex and their poverty. What path is open to them? In this project, it was important for the artist to show the girls as big, nearly bigger than life-size. “The girls become more frightening like that,” says O Zhang. “You have to see them, you cannot ignore them.” This is the conceptual articulation of the work that O Zhang presents to us. An image can be beautiful. And O Zhang offers that, because she has the technical tools to imbue us with beauty and to subdue us into her narrative. After completing a BA in art at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, she went to London to follow her dream of knowing the world. In the process, she also managed to obtain a professional education in photography, to experiment with films and videos and to engage in writing and creating installations. Her career path, unusual for a young Chinese artist, eventually led her back to China for the specific project, Horizon. She wanted to explore her cross-cultural identity, which, in her case, she had managed to avoid being ghettoized between East and West. From a very early age, she had confronted the cultural, linguistic and ethnic differences existing in China. Her journey between Guangzhou, Hunan and Beijing helped to shape her character and taught her the complexity and resourcefulness of China. In London, she had to adjust to new cultural and social codes. New York placed her in one of the world’s most aggressive professional environments. Horizon was the seminal project by which she could take some distance to understand where she came from and how her own horizons shaped her. She could then look again at China and coldly, without flourish, present it to us. There are neither romanticism nor extravagances in her approach, just a scalpel-sharp look at a forgotten China. The little girls have to find a future. We cannot offer one to them. But, can we even offer one to ourselves? O Zhang’s photographs are poignant, because they confront us with the questioning gaze of the girls and our own helplessness. What a contrast O Zhang offers us with her conceptual photographic project The World is Yours (But Also Ours)! Here, teenage girls and boys, selected by the artist, symbolize the hopes and dreams of a country preparing to present itself to the world. The photographs were taken during the two months preceding the opening of the Olympic games in Beijing in 2008. The montage of the images vividly depicts the ambiguities of a nation caught between the fast growth of a capitalist economy and a communist legacy. As the artist points out in the introduction to the catalogue for the project: “ China is now developing more rapidly than ever before and in every different way with what could be seen as its second ‘Great Leap Forward’”. The images are composed like the propaganda posters of the Cultural Revolution: each picture with a slogan at the bottom. In contrast to the revolutionary posters, the slogans here are borrowed from different sources. Quotations from the Little Red Book echo the present with references to advertising and sports. The entire composition records the changes that China is going through. And these changes do not only affect the history of the country, they are having an impact on world history. To enhance the polyvalence, O Zhang plays with languages. The quotations are written in Chinese and can therefore only be deciphered by those who can read Chinese. In the images, young girls and boys wear T-shirts with hilarious messages in Chinglish. O Zhang bought the T-shirts in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. The messages in English are often not understood by the people wearing them, but the fact that the clothes are successful demonstrates a desire of Chinese people to be part of a more universal world. Or they simply like the design and want to be cool. The text on the T-shirts becomes irrelevant. The actual words are extraneous. It is the Chinglish that becomes relevant. It is no longer just a bad translation. It marks inter-connectivity between people all over the world. O Zhang’s choice of political quotations from the Cultural Revolution is not insignificant. She shot the pictures at a moment of high national pride. There is also a link to her past and the past of her parents in the village of Jishou in the Hunan Province during the Cultural Revolution. Today, there is more freedom in China, but the rules are still defined by a unique party. Advertising slogans reveal the new codes practiced by Chinese youth. The slogans are the expression of their desires and the way they are transforming the society. In opposition to the little girls of Horizon, these city youths perform in an exuberant environment. For that reason, O Zhang staged them in front of a recognizable icon or space: Tian’anmen Square, the Olympic Stadium in Beijing (the Bird’s Nest), the monument of the People’s Heroes. Looking at Salute to the Patriot shows how the artist constructs a scene by juxtaposing layers. “It’s All Good in the Hood” proclaims the T-shirt, probably reassuring that all is good that ends well, especially when the political structure has erased any memory of what happened in June 1989 on Tian’anmen Square. The girl is too young to know. And why should she know? She belongs to the one-child policy and she has every opportunity in front of her. O Zhang takes her portrait from below, making her taller, giving her power, promising her a future. The texts in Chinese join the global smorgasbord. Once, they united a nation, but today, they sound as though they were found in an archeological dig. The title photograph of the series The World isYours, and Also Ours refers to a speech by Mao Zedong to Chinese youth in 1957. As O Zhang says in her catalog, the sentence pronounced by Mao is much longer and catches the incredibly long message written on the T-shirt.

Mao told the youth, “The World is yours, as well as ours, but in the last analysis, it is yours. You young people, full of vigor and vitality, are in the bloom of life, like the sun at eight or nine in the morning. Our hope is placed on you…” The T-shirt responds, “Thow Your Hand Up CHINA. Looking inti my eyes touch my heart. Don’t know why. You never gonna stay in sight . I just wanna know what the hell is goin’ down. You’d better change your stupid ways. Give Me Sight To See Inside.” The heaviness of the Cultural Revolution contrasts with the whimsical verse of a nearly hip-hop contemporary message. The erected symbolic right arm of a concrete statue of Mao seems to be weighing on the girl’s posture. She appears to be hunching her shoulders in front of such wordy nonsense.

Be Refreshingly Cool is Up to Me refers to a slogan used by Coca Cola in China in 2005. This sentence entered into the vocabulary of the youth, expressing individualism. Here too, we have a right arm lifting up. But, this is not Mao’s arm. The robot gives strength to a boy, whose T-shirt proclaims “Microarray Technology? Piece of Cake!!!” Easy to understand when we know that in 2008 China Internet users surpassed the number in the United States. The World is Yours, (But Also Ours) is the world that O Zhang perceived at that time. She was there, in Beijing, in 2008, at a moment of intense exhilaration and she responded to all the codes and symbols used in the propaganda. She caught the game being created between the juxtaposition of different cultures: the American culture, the Chinese culture, the capitalist culture, the Disney culture, the Confucian culture…The result is a conceptual positioning of her work. “The project is not a social documentary,” says Glenn McMillan, a partner at CRG Gallery in New York. “It is art because it is not locked down. You have a sense that O Zhang is saying something, she has an ethic in her work, and you never feel that she is lecturing you. There is an open end with her. You are taken on a path from which you can branch out to other paths.” Ambivalence, O Zhang’s main topic for exploration, comes into its own with the project Daddy and I, a photographic series realized between 2005-2006. The idea was to photograph American families who have adopted a Chinese girl. China’s International Adoption Program was put into effect fully in 1992. Since then, more than 55,000 Chinese children –almost all girls- have been adopted. O Zhang took advantage of the fact that taking a family portrait by a professional photographer is quite common in America. She thus posted an ad on an online adoption center asking families to have their portrait done. There was a twist in her request: the photograph should be about the adopted Chinese girl and the American father. The reaction of the families was quite positive. Families were pleased to have a nice picture taken by a professional photographer. In this project, however, the real concept was to capture the relationship between a young Chinese girl and the aging American father. The photographs were taken in wealthy suburban areas: New York, New Jersey, Connecticut and Oregon. They were shot in gardens giving a sort of Oriental aura to the general atmosphere, especially with this photograph taken under a cherry blossom tree.

Daddy and I is about identity. The girl is growing up in a transplanted environment and she has very quickly assimilated the rules of the American Way of Life. She lives a comfortable life, thinks about her education, her career, plays with other kids, shares common denominators with any American girl. O Zhang superbly captures this in her photographs. The girl is becoming independent although we know that underlying currents may already interfere with her innocent life. What is it to be Chinese and/or Chinese American? In the paradise-like environment, the father tries to play the role model. In some images, he cuddles the girl, in others, he poses as a reassuring symbolic figure. This series takes us down a very slippery slope. What is our reaction when we see an aging man walking in the streets of New York (and by the way it could just as well be Paris) with a beautiful teenage Oriental girl clinging to his arm? We could easily come to a wrong conclusion. “I do not want to be educational and say that something is bad,” O Zhang said, when we interviewed her at her studio in Brooklyn. “People can look at things at a different angle and they can think about them. In the ‘Daddy and I’ photographs, I feel as though I have to present things differently and people can have their own explanation about it.” The photographs, taken in vibrant colors, describe an idyllic situation: a love relationship between a father and a daughter. Because of the saturation due to the exposure and the use of a flash, most of the viewers believe that the father and daughter look like fake flowers! An “innocent” photograph takes a surprising turn. O Zhang works in a seductive way. We have at first a beautiful photograph with the quality of a fairy tale. A picture that is presented in a certain way, but that really means something else. By creating a path between what she is saying and what we see, between fiction and reality, the artist plays with the nature of ambiguity.

O Zhang belongs to a generation of artists that communicate their way of life and the fact that they belong to an international community. She proudly states that she is very Chinese in her heart. She also knows that western culture has influenced her Chinese character. “It is not a conflict for me,” affirms the artist. “This environment is just natural for me. It does not have to be always East and West. For me, it is just one thing: the world is flat, people are getting closer. Differences between countries are getting smaller.” Like many artists today, O Zhang does not want to be categorized. She does photography, but she does not want necessarily be presented in photography galleries. She addresses big cultural issues. She feels at ease and happy to be represented by a New York-based gallery not specialized in contemporary Chinese art. CRG Gallery, a gallery in the heart of Chelsea, is interested in her work because she reflects the world of today. I asked Glenn McMillan, a partner at CRG Gallery to describe O Zhang: “ O Zhang is unbelievably energetic and ambitious in a positive way. She has a great deal of confidence. She is not arrogant. Her diligence and focus are admirable. You need that to be successful. She is obviously intelligent. She is obviously focused. She is very convinced of what she is doing. You need that to be an artist. She is critical of what she produces. She needs to have conviction for the kind of projects she undertakes. O Zhang is very interesting to us, because she is reflecting the world of today and she does that from multiple positions: being here, being part of the New York community, but at the same time coming from a Chinese background. She has an awareness of what is traditional China. Going to London, she obtained a Eurocentric education. She is thus dynamic in that way. Ai WeiWei lives in China and that works for him. But we are looking for a point between two worlds. O Zhang perfectly fits that with our gallery.” Issues of cross-culture and identity were explored in an ambitious project commissioned by Queens Museum in New York to mark the 70th anniversary of the 1939 New York World’s Fair, a time when the country was at the peak of the Great Depression. For that reason, the fair was devoted to the future. The world’s fair was conceived by a group of retired New York businessmen, who decided to lift the city’s spirit and to encourage countries of the world to look at the future. The 1939 opening slogan “Dawn of a New Day” responds as if by resonance to the 2009 exhibition entitled Cutting the Blaze to New Frontiers, which itself is O Zhang’s reworking of the motto that was on the DuPont pavilion in 1939, “Blazing the Trail to New Frontiers Through Chemistry.” As part of the museum’s inaugural artist in residence program, O Zhang wanted to construct a mini world fair with a group of young teenagers of immigrant parents, residing in Queens. “What inspired me is the history of the museum,” O Zhang said. “I am always interested in the relationship between history and the present. This project is about that. In 1939, a world’s fair took place in Queens. It was still the time of the Great Depression. When I started the project, it was 2008, the year of the great recession. The link was there, historically, and I started to map the project.”

In this project, it was also a question of scale. A world’s fair is big and is architecturally designed around national pavilions. It is a projection of the best a country has to offer to the world. The evaluation is based on technical innovations and on the presentation of traditions. For O Zhang’s project, there was not enough money to organize a large event. She reflected on the diversity of Queens, the most ethnically diverse urban area in the world. According to the U.S. Bureau of Statistics, 46% of the population in Queens is foreign-born. What interested her was the idea of working with children who were born in the U.S., and are consequently American by birth, but whose immigrant parents had to flee their country and cannot or do not want to go back. The kids had to create their own mini pavilion based on their own imagination and on their parents’ stories. In this respect, the project was educational, because the kids had to communicate with their parents and extract stories that their parents had never told them before. For O Zhang it was a matter of seeing how the homeland was imagined by the youths and how it was experienced by the parents. The communication between the two generations became instrumental to pass on or to define where people came from.

Sixteen miniature national pavilions represented countries such as Jamaica, Cuba, Pakistan, China, India… In the end, it was a representation of origin and heritage. When I asked O Zhang if this project makes her think about her own motherland, her answer was that it touches on human imagination. “How do you imagine a place you have never been to? Especially when that place is your motherland. It is like: how you do imagine your mom when you have never seen your mother? I have been in China. I was born there. It has some kind of East/West influences. For example, for ABC people (American Born Chinese). How do they think about themselves? Are they American, Chinese? What do they think about China? These things happen to my life too. Many Chinese have never been to America, but they always talk about America. How do you imagine a country you have never seen? That is human imagination and that can be a piece of art.”

The 1939 World’s Fair looked at a future constructed around tools and machines to better help innovative ideas. O Zhang’ concept was to bridge historical and personal currents to better integrate experience. She even went further by creating an open space allowing visitors to write on a wooden chip what they do not wish for the future generations. This box of non-wishes was burned at the end of the exhibition as if exorcizing our fears and doubts. The idea works here in opposition to the Westinghouse Time Capsule that was buried after the 1939 World’s Fair. The Capsule contains the memories of an epoch (Albert Einstein’s and Thomas Mann’s writings, a Mickey Mouse watch, seeds of cereals commonly used at the time such as wheat, corn, oats, and many other relics.) The Capsule works as a time reference to be open in 5,000 years. The dreams of an entire generation will be deciphered (even in a wrong way, but this is irrelevant.) The burning of the wooden chips evaporates in strata that we, hopefully, will never catch. It is our act of faith, our prophesy for future generations.

Connecting a story to the history of a place took O Zhang on a very emotional path after being invited to participate in Fokus Lodz Biennale 2010, in Poland. It was a project that took a long time to prepare, because most of the artists had to create a work on-site. It took six months for O Zhang to reflect and to produce the work. She discovered that there had been a ghetto in Lodz. It was the second largest one established for Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland. She found an archival picture of a couple posing behind a shoebox. She read the poignant story attached to the picture. Leon Jakubowicz, a shoemaker, redesigned a large shoebox in the shape of the wings of a dove. Inside the wings, he drew the map of the ghetto. Then Leon and his wife, Rachela Zylber, posed behind the dove-like box. What struck O Zhang was that the couple is smiling and that it took the time to project an image of serenity and confidence while atrocities were embracing the ghetto. “The couple is proud about the art they have made, even though it is a map of the ghetto,” confides O Zhang. “I like that human spirit. A human spirit of creativity. Creativity is everything. It can conquer death. Their smile is so beautiful. They are posing like they were angels.” Rachela is presumed to have perished in Birkenau. Leon was sent to a forced-labor camp in Germany and survived. His brothers brought him the model of the box that Leon buried in the basement of the shop. Leon emigrated to the USA in 1958. He brought with him the box, which is now at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC. (for the history and more images, go to

O Zhang recreated the shape of the box and placed it in an old empty shoe shop in the city of Lodz. She called the project The Dove of Lodz, as a way to connect the old story with the new framework of the city of Lodz. She used the same outline, but drew the new city plan. Then, she turned the shop into a photo studio and invited people to come and pose with the box. She did not give any instruction to people, but an assistant handed out a brochure with a copy of the original photo and the description of her work to visitors at the entrance. She took two photos each time. One that people could take back home. One that she put on a wall to reconstruct the shape of a dove. The final composition became a peaceful symbol of unification of people through adversity. O Zhang wanted to pass on the optimism about creativity. “For me,” she says, “it is as though the human spirit cannot be broken. No matter what, people have still creativity. You cannot be broken by any circumstances.” A lesson she already learned through her parents. The Dove of Lodz shows the history of real people: the people of the ghetto and the passers-by of the Biennale. It is not a question of re-enacting an event. It is impossible to recreate reality, but O Zhang sets the conditions to encompass artificial scenes based on reality.

In her work, O Zhang opens the door to personal interpretation. At a quick glance, her photographs appear to present attractive images that might belong in a fairy tale, but we soon realize that there are other stories below the surface and that they are there for us to discover. There is the reality captured in the image, and then there is the deeper, more vibrant and subtle reality actually being lived by the subjects momentarily reflected in the image. The questions remain for us: Is what we see a fiction or a reality? Which paths do we take? How do we allow our stereotypes to infringe on the interpretation of our own reality? O Zhang's photographs challenge the horizons we have built to appease our own uncertainties.

|

||||||||||||||||||